Many experts agree that IBP has a monthly check and balance with the budget and the...

PREVIEW

PREVIEW

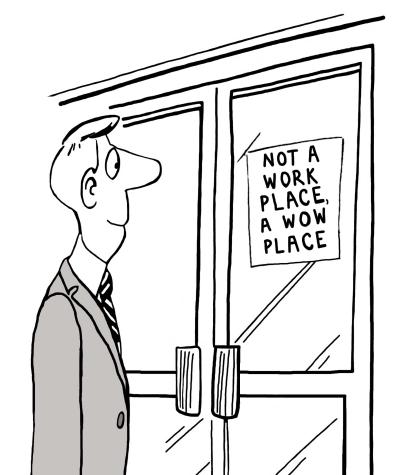

Successful execution of FP&A is inevitably linked to corporate culture. A culture based on a silo mentality and lack of trust not only undermines integrated FP&A effectiveness but also reduces employee engagement and well-being. In this article, Niels van Hove argues that while effective integrated FP&A can thrive in the right company culture, the FP&A process itself can influence and shape that culture. He calls for FP&A leaders to articulate goals that include clear expectations on behaviours. Doing so will not only improve effectiveness but also enable FP&A to play an active role in improving employee attitudes and satisfaction.

Key points

-

The organisational mindset has a huge impact on integrated FP&A performance. However, certain mindsets have proven to be more effective for individual and corporate well-being and performance. Among them are positivity, a growth mindset, and mental toughness.

-

Many integrated FP&A initiatives fail, get stuck, or move slowly. Company culture and behaviour are likely the primary reasons behind this.

-

Executives can’t assume they have the right company culture to implement effective integrated FP&A. Rather, they need to define their expectations for participant behaviours clearly. Trust is paramount, and behaviours that improve trust should be prioritised by executives.

-

Culture-change efforts are most successful when fully integrated into a business initiative. The CEO is advised to use the FP&A cycle to display, manage, and nurture effective behaviours actively.

Introduction

Integrated FP&A implementations require significant change, not the least being the behavioural change. And change is hard. In his groundbreaking 1996 study Leading Change, John Kotter reports that change transformation is successful in only 30 per cent of companies. A McKinsey study among 3,199 CEOs in 2008 confirmed that, indeed, only one in three transformations succeeds (Aiken & Keller, 2009).

And of the failures, 70 per cent are due to culture-related issues: employee resistance to change and unsupportive management behaviours (Aiken & Keller, 2011). It is not unlikely that a lack of attention to behaviours is a major reason why integrated planning initiatives fail. But rather than seeing behaviours and company culture as obstacles to implementing and developing integrated FP&A, we should view the FP&A process as an opportunity to shape and improve company culture.

Executives need to align themselves around what effective mindset and behaviours to integrate into their company culture. If they should aspire to achieve high levels of integrated FP&A maturity, the FP&A cycle can play a critical role in establishing this culture. First, executives need an understanding of what these effective mindsets and behaviours are—and need to demonstrate these behaviours themselves.

Effective Mindsets

In an extensive review of sales and operations planning literature, Tuomikangas and Kaipia (2014) list culture and leadership as one of six requirements to improve performance. Key points here they include “the organisational mindset and practices that facilitate and advance formal planning.” In terms of individual and organisational mindsets, psychology explains how some mindsets are more effective than others.

Positivity

Martin Seligman (1998) shows that individuals with a positive mindset are less depressed, live healthier, and perform better than people with a negative mindset. In one study in an insurance company, the 10% of most positive salespersons sold 88% more policies than the 10% of most negative sales personnel. Positivity can be influenced: one of the most significant findings in psychology in the last 20 years is that individuals can choose the way they think.

Growth

Another superior trait is the growth mindset versus the fixed mindset. Carol Dweck has shown that people with a fixed mindset believe their talent and capabilities in life are a given, and not many things can be done about them. People with a growth mindset believe that every skill can be trained and feel they are the master of their destiny. Dweck’s decades of research and many experiments show two crucial things: first, people can be influenced to adopt a growth mindset over a fixed mindset before they take on a task; and second, individuals or groups having a growth mindset almost always outperform those who do not (Dweck, 2006).

Mental Toughness

The mindset of elite athletes is often referred to as a differentiator between winning or losing. Performance psychologist and practitioner Jim Loehr (1995) called the mindset of the winner mental toughness, a concept that has been successfully used in elite sports coaching for the last 30 years. Peter Clough identified control, commitment, challenge, and confidence as the underlying attributes of mental toughness. Research shows that mentally tough individuals are committed, proactive, open to change, physically and mentally healthier, and perform up to 25% better (Clough & Strycharczyk, 2012). In my own online research, practitioners indicate that effective integrated planning processes show more of the behaviours linked to these attributes of mental toughness (Van Hove, 2017). All these mindsets can be measured and supported in the FP&A cycle.

Effective Organisational Behaviours

There can hardly be any doubt that effective behaviours result in improved integrated planning and company performance. These behaviours include commitment, trust, top management acting as a role model, a collaborative spirit, empowerment, constructive engagement, and competence in dealing with conflict (Tuomikangas & Kaipia, 2014). Empirical evidence for effective behaviours was reported in a McKinsey survey of 189,000 people in 81 diverse organisations (Fesser, Mayol, & Srinivasan, 2015). That survey found that four leadership behaviours explain 89 per cent of the variance between strong and weak organisations. These organisations differed significantly not only in terms of leadership effectiveness but also on McKinsey’s organisational health index, which measures supportiveness, the strength of the results orientation, the seeking of different perspectives, and the effectiveness of problem-solving.

Four Main Constructive Behaviors

Even more significant empirical evidence is found by Robert A. Cooke and J. Clayton Lafferty (2014). Based on the survey of 1 million managers and 12,000 organisations worldwide, they conclude that there are four main constructive behaviours that support effective management across geographical boundaries: achievement, self-actualisation, humanistic encouragement, and affiliation. These four behaviours not only help to better-integrated planning by improving motivation, work relationships, external adaptability, and interunit coordination but also give greater life satisfaction and well-being to the individuals who display them.

-

Achievement: People with this behaviour have a tendency to set challenging yet realistic goals. They link outcomes to their efforts, not to chance. They also think ahead, plan, and explore alternatives before acting, and learn from their mistakes.

-

Self-actualisation: Self-actualised people have a strong desire to learn and experience things. They are creative and, at the same time, realistic, with a balanced concern for people and tasks.

- Humanistic Encouragement: Individuals with this behaviour have an interest in the growth and development of others and are sensitive to others’ needs. Further, they devote an extensive amount of their energy to coaching and counselling others. They are thoughtful and considerate and provide others with support and encouragement.

- Affiliation: People with a keen sense of affiliation have an interest in developing and sustaining good relationships with others. They share their thoughts and feelings, are friendly and cooperative, and make others feel a part of the team.

Trust Is Paramount

Although no single behaviour is most effective for every business, trust seems to be a recurring and paramount theme. Trust is the first thing people seek when meeting someone new (Cuddy, 2015). A team without trust fears conflict lacks commitment, avoids accountability, and suffers from inattention to results (Lencioni, 2002). Studies have reported that trust has a direct impact on strategy execution, is one of the most important predictors of positive organisational outcomes and positively affects psychological well-being. When leaders display trust behaviours, they increase psychological safety, a shared belief where team members feel accepted and respected, and a study by Google of over 180 organisations reported that psychological safety is by far the most significant contributor to team effectiveness (Rozovsky, 2015). The latest research from neuroscientists focuses on eight measurable behaviours that most stimulate trust (Zak, 2017). Zak found that, compared to low-trust companies, people at high-trust companies report 74% less stress, 106% more energy at work, 50% higher productivity and 29% more satisfaction with their lives.

All of this shows that there are mindsets and behaviours that are superior in terms of integrated planning effectiveness, business performance, and employee well-being. Executives can use this knowledge to include the behavioural change in their integrated business FP&A initiatives and would be wise to emphasise trust-building behaviours.

Combining an FP&A Cycle and Behavioral Change

If executives wish integrated FP&A to be successful and lasting while at the same time improving company culture, effective behaviours need to be embedded in their planning initiatives. As Collins & Porras (1996) note, “Embedded company behaviours will drive a sustainable company culture, which will last over time.”

Executives can’t simply assume their company has the right mindset and behaviours to implement effective and sustainable FP&A. Neither can they believe behaviours will automatically change for the better because of the implementation of integrated planning. Although the integrated business process can indeed support improved teamwork, we can’t assume this due to the complexity of individual behavioural preferences and company culture. An employee who has developed distrust or other defensive behaviours over a whole lifetime will not simply shed these behaviours when a new FP&A cycle is implemented. Similarly, a company culture of distrust, fear or lack of psychological safety will not change without a significant cultural change effort on top of the integrated FP&A change program.

Combine Business Initiatives

There is evidence that cultural change efforts are most successful when fully integrated into a business initiative (Dewar & Kellar, 2012). This is a very important notion; it means executives can define what effective organisational mindset and behaviours they want to pursue and use the new FP&A cycle to carry some of the weight of this cultural change.

A CEO will often delegate change management for the cultural initiative to Human Resources. HR will develop a change program; define the cultural baseline, measurements, and goals; provide training or coaching, and develop internal communication about the initiative. HR could further update job descriptions, recruitment and induction policies, training and development materials, and reward and recognition schemes. However, the cultural initiative is more likely to succeed if it is integrated with another business initiative. A CEO can take a direct lead in both the FP&A and the cultural business initiative and use the FP&A cycle meetings to display, monitor, measure, improve, and nurture preferred behaviours.

In a well-established periodic FP&A process, the meetings should be the only management gathering where important future decisions will be formed about the annual operation plan, strategy, budgets and resource allocation. These decisions will sometimes be made under time pressure and stress, and it is during these moments when individuals fall back on their default behaviours, becoming defensive or aggressive.

Kotter (1995) and others argue that change is best established when executive leaders “walk the walk and talk the talk.” A CEO should use the executive meeting in the integrated FP&A cycle to set a behavioural example as well as clear expectations to his team, all the more so during stressful moments. I’ve facilitated executive meetings where the CEO would stop the meeting if emotions got out of hand. The language used in the meeting was not aligned with “show respect” or “provide constructive feedback.” Following time to reflect, the meeting would continue, and, afterwards, a roundtable of feedback would include comments about behaviours displayed.

An integrated FP&A cycle contains quarterly, monthly, and sometimes even weekly planning meetings and includes many senior stakeholders from most business functions. The influence of the planning cycle can go across business units and countries and even be global. A CEO can set the expectation that every FP&A meeting in every business unit or country takes the time to reflect on agreed behaviours and provide feedback during the executive meeting. In this way, a CEO can utilise the FP&A cycle across echelons, functions, business units, and countries to drive preferred behaviours— behaviours that, over time, become part of company culture.

Increase Executive Engagement

Executive engagement in an integrated FP&A cycle is critical. Done well, an FP&A cycle provides support to an organisation to deploy and execute its strategy. Suppose the cycle outcomes are clearly communicated, and executives continually update strategy and forecast. In that case, business goals are better understood, and employees clearly understand how their job contributes to strategy and meeting budget requirements. These outcomes are among the most impactful employee-engagement drivers (HBR, 2013). The argument that an FP&A cycle improves strategy execution and employee engagement can be a solid case to make executives become change agents.

However, by making the FP&A cycle include a cultural change initiative, a CEO can increase the status of the program and create more executive engagement. It’s likely that HR, in turn, will show increased engagement with FP&A through its role. On top of this, when a CEO drives the right behaviours, the planning cycle over time becomes more effective and more valuable for all executives. If the behaviours include increased trust levels, additional benefits will accrue in terms of increased earnings, reduced employee stress, more energy, higher productivity and increased life satisfaction.

In my earlier Foresight article (Van Hove, 2016), I suggested that the ultimate goal of integrated planning is the generation of a plan to support an organisation’s efforts to deploy and execute its strategy. With a combined FP&A and cultural initiative, we can say that integrated FP&A improves not only strategy execution but also employee engagement and psychological well-being. For all these compelling reasons, there is no excuse for an executive not to be engaged with integrated FP&A.

SUMMARY

To be most effective, integrated FP&A requires a positive, growth-oriented, mentally tough mindset as well as constructive behaviours. It is unlikely that a critical mass of effective behaviours is present in every company. Where it is not, integrated FP&A implementations also require that executives endorse behavioural change. Once FP&A reaches a certain maturity and level of integration, it can be used to support or instil appropriate behaviours in company culture. Rather than being dependent on the company culture for its implementation, the FP&A cycle offers a CEO the means to influence company culture with the result of improved employee engagement and psychological well-being.

This is an amended version of a Foresight article.

Subscribe to

FP&A Trends Digest

We will regularly update you on the latest trends and developments in FP&A. Take the opportunity to have articles written by finance thought leaders delivered directly to your inbox; watch compelling webinars; connect with like-minded professionals; and become a part of our global community.