In this article, the author examines the FP&A's role in helping businesses win by measuring financial...

My previous article examined the role of Financial Planning and Analysis (FP&A) and how they can help businesses by measuring capital allocation and understanding the business life cycle. This article continues the discussion on how we can help our organisations measure information that balances the trade-offs between profitability and innovation.

A New Way to Look at Numbers

In Safi Bahcall's book “Loonshots: Nurture the Crazy Ideas That Win Wars, Cure Diseases, and Transform Industries”, the author explains that long-term sustainable success is built by entrepreneurs who develop a unique structure to nurture the development of new ideas inspiring innovation. These entrepreneurs are careful gardeners who cultivate systems defined by a standard set of principles. Crediting the historically revolutionary success of Vannevar Bush and Theodore Vail as careful gardeners, Bahcall names these principles the “Bush-Vail” rules. FP&A teams can provide superior metrics by understanding these rules and how to measure them.

Rule 1: Separate the Phases

Bahcall defines two distinct organisational phases - artists (innovators) and soldiers (doers). Artists are responsible for innovation, while soldiers execute the day-to-day operations associated with large-scale production. Business leaders should understand that artists and soldiers serve drastically different functions and, therefore, require different types of managerial support. Artists require loose controls and creative metrics, whereas soldiers require tight controls and quantitative metrics.

FP&A Tip:

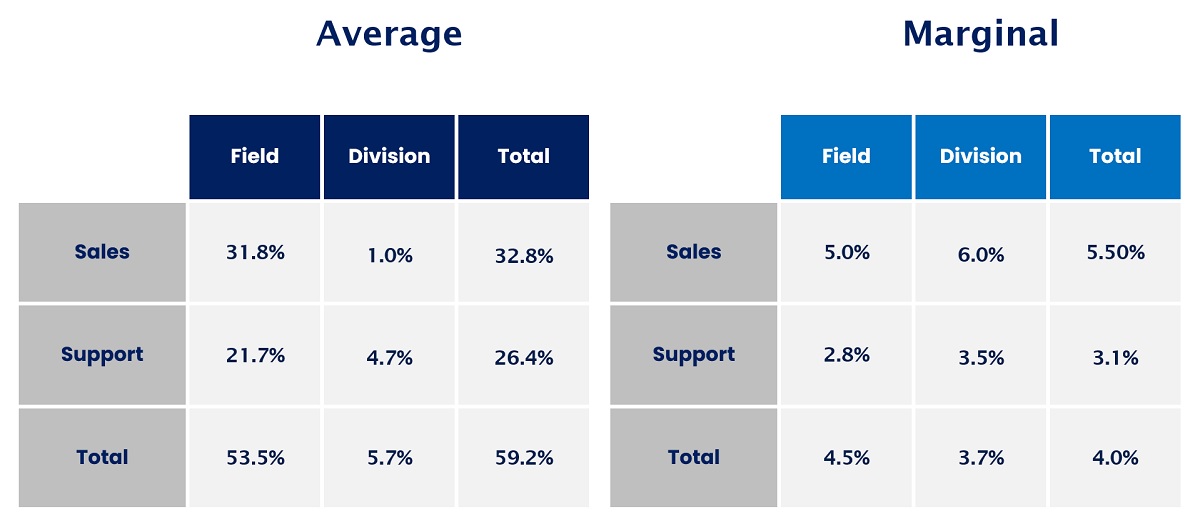

It is crucial to recognise that artists and soldiers cannot be measured in the same way. This separation is often seen between centralised management teams that handle divisional macro numbers and decentralised business unit managers in the field. We also see it when we monitor the production (sales) team and non-production (service) teams. They require different metrics to measure performance since macro levers are different from micro levers. For example, know your average numbers. However, be able to differentiate numbers and know your marginal costs (changes in resource allocation) to influence decision-making.

Figure 1: Illustrative example of average and marginal costs

Rule 2: Create a dynamic equilibrium

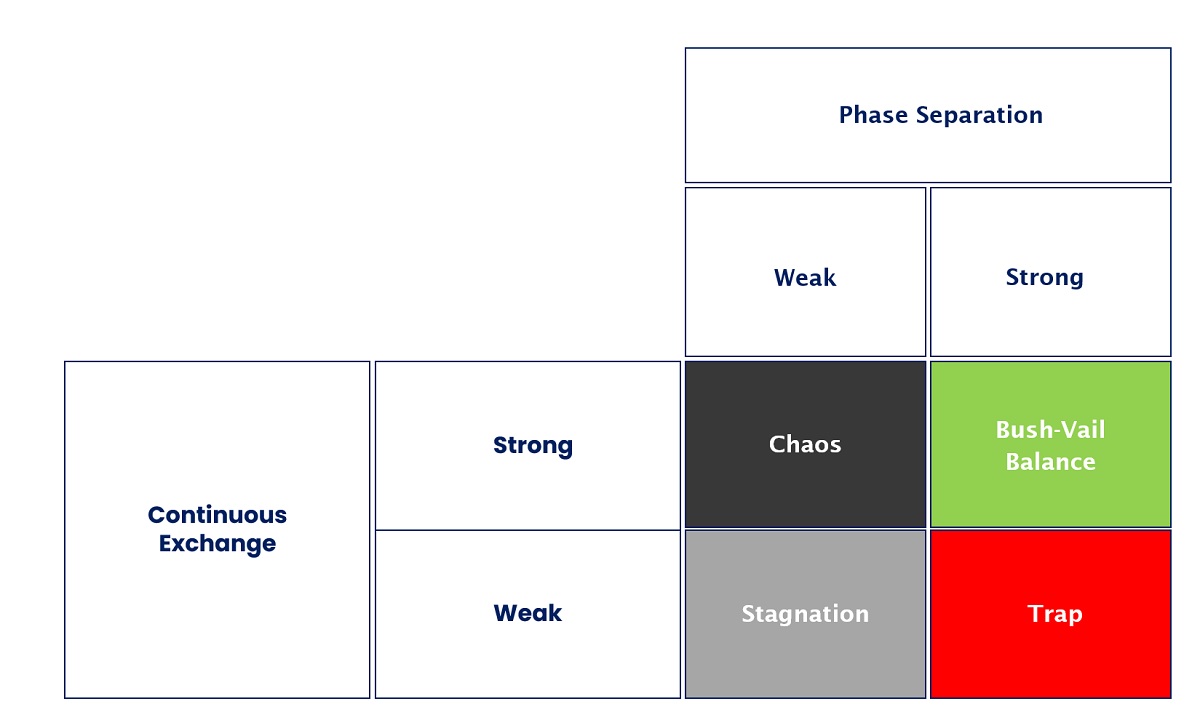

There is a natural conflict between artists and soldiers. Leaders must manage that conflict and provide equal opportunities, respect, and appreciation to both groups regardless of their organisational role. It is important to appoint and train project champions who can bridge the divide between artists and soldiers. Artists may have unrealistic expectations regarding their innovation attempts, while soldiers may be focused on the shortcomings of those innovations. Leaders must identify and appoint metaphorically “bilingual” specialists who can understand both perspectives and bridge the divide. FP&A professionals are well-suited to act as conduits between artists and soldiers as we review metrics from different angles and develop relationships with both artists and soldiers. The diagram below shows how to achieve a good Bush-Vail balance.

Figure 2: Achieving a good Bush-Vail balance

- When there is a weak separation between artists and soldiers and a weak exchange of ideas, we are susceptible to no innovation.

- When there is a good exchange of ideas but no separation, we lack a process to implement ideas and end up with chaos.

- When there is a strong separation and a weak exchange, this is called the trap. That’s where senior management is selecting which ideas will win without being fully open to alternative ideas. Think of Blockbuster Video failing to invest in streaming videos.

- What we want is a strong separation and robust ideas to facilitate a Bush-Vail balance.

FP&A Tip:

While it is difficult to measure the diagram above, being aware of this paradigm and how it impacts strategic projects businesses are trying to implement can help us understand where we are and where we want to be. Don’t be afraid to adjust how we measure initiatives to help achieve a better balance.

Rule 3: Spread a System Mindset

A system mindset involves a careful examination of decisions’ quality instead of analysing just their outcome. A failed outcome, for example, does not necessarily mean the decision or the process behind it was bad. There are good decisions with bad outcomes. Those are intelligent, well-taken risks that didn’t play out. For example, if only three lottery tickets are sold, one of which will win, then purchasing one of those is a good decision, even if you end up holding one of the two that didn’t win. In such conditions, you always make decisions play even when you are likely to lose (66%) because winning offers superior returns. Teams with the outcome mindset focus solely on specific projects or strategies and evaluate failure based on their consequence. On the other hand, teams with a system mindset consider failure beyond one specific result and delve into the decision-making process. They ask questions such as "How did we arrive at this decision? Should different people be involved in different capacities? Do our incentives affect the decision-making process? Should we alter how we evaluate project opportunities in the future?" and so on.

FP&A Tip:

Adopting a system mindset is crucial for FP&A teams, as it allows for a deeper understanding of the decision-making process and how it can be improved. When measuring things, comment on the quality of the underlying processes and check if there are lessons learned from any failures. For example, measure employee turnover and track regrettable vs. non-regrettable leaves and their influence on competition percentage instead of measuring the latter. Know your drivers, not just your P&L.

Rule 4: Raise the Magic Number

Bahcall introduces the concept of the Magic Number, which represents the number of people in a group where employees can focus on projected success rather than politics. For example, let’s say an employee works a normal 8-hour day. The employees need to decide if they spend the final hour of the day on work that might increase the value of projects or networking and promoting themselves within the company. It’s easy to see that both are critical to team success. However, the ratio between the two needs to be balanced.

FP&A Tip:

You can calculate your management number using this formula: M = (E *S ^2 * F)/G

- M is the Magic Number of people in a group

- E = Equity fraction – how much bonus/equity is relative to salary

- S = Management Span – number of direct reports per manager

- F = Organisational Fitness

- G = Salary growth rate according to the the hierarchy

How it works

Since the equity fraction (E) is the numerator, the Magic Number gets bigger as E increases. That means an increasingly large group of people can work free of politics in the loonshot phase. That makes sense since a greater equity stake encourages spending time on projects rather than politics. The management span (S) is also in the numerator at a double power. Increasing the management span reduces the number of layers, which in turn reduces the importance of politics. It also increases an employee's stake in project outcomes. Both favour focusing on loonshots rather than career interests. As the salary step-up (G) increases, however, the opposite happens. Large salary step-ups encourage politics, as employees compete to curry favour and win giant salary increases. That decreases the maximum number of people (M) who can work together in the loonshot phase. The last factor is the organisational fitness (F). Suppose companies can create review systems against politics, invest in developing their employees' skills, and do a good job in matching employees with projects that allow their skills to shine. In that case, those companies will increase their likelihood of nurturing loonshots.

Conclusion

The Bush-Vail rules are a creative way for FP&A teams to analyse financial results by separating numbers into different groups, managing average and marginal costs, developing a system mindset, and understanding group sizes' impact on incentives.

Subscribe to

FP&A Trends Digest

We will regularly update you on the latest trends and developments in FP&A. Take the opportunity to have articles written by finance thought leaders delivered directly to your inbox; watch compelling webinars; connect with like-minded professionals; and become a part of our global community.