In this video, Robert Ycmat, Chief Financial Officer (CFO) at Revere Health, shares the FP&A workflow...

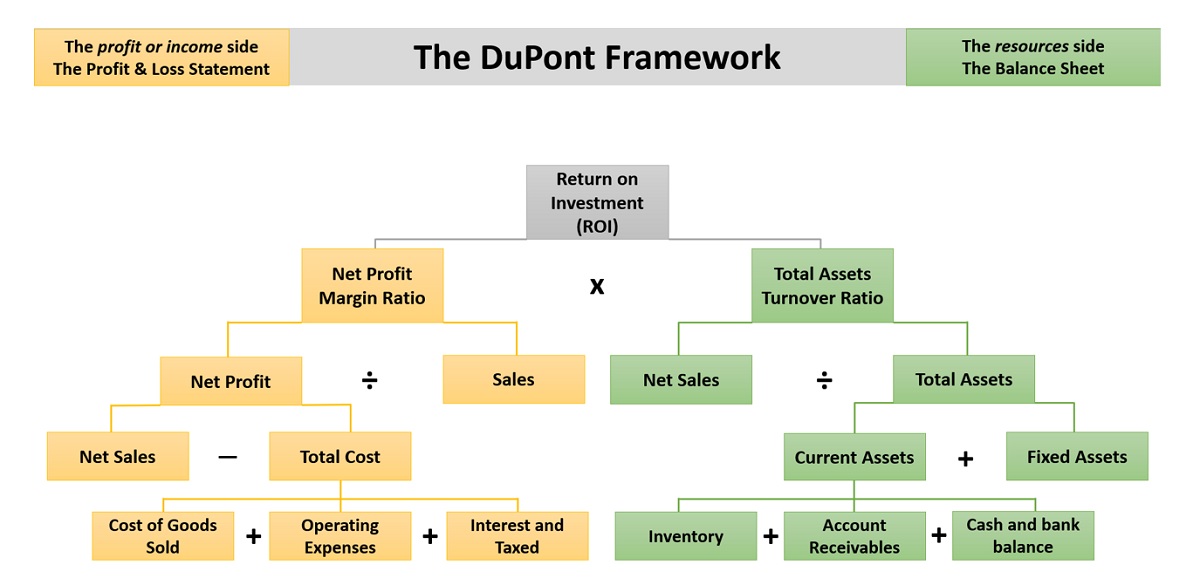

Profitability Analysis is linked to value creation. Any business wants to make a financial return on its resources to provide customers with goods and services.

Why Is Profitability Analysis a Relevant Topic for FP&A?

A basic representation of this idea is shown below using the DuPont framework. The left side represents the profit or income part, also known as the profit & loss statement. The right side represents the resources side or the balance sheet.

Figure 1: The Dupont Framework for Profitability Analysis

Profitability is not the same as return. Profitability is determined by business models, market sectors and internal organisational capabilities. In contrast, return is determined by the broader economy, credit availability, alternative business opportunities and the business owners’ expectations.

The DuPont framework applies to the overall business. However, unless a company has one product or serves only one customer, there is usually a portfolio of assets. The portfolio nature of the business requires deeper Profitability Analysis. This is relevant to FP&A because it supports allocating resources to each part of the portfolio.

Four Types of Profitability Analysis: Purpose and Definitions

Imagine a business that sells products or provides services to customers through various sales channels across multiple countries.

This setup requires at least four types of Profitability Analysis.

- Product

- Customer

- Market

- Sales channel

Two things are critical to keep in mind:

- the purpose of the analysis

- the definition of profitability

The Purpose of the Analysis

What is the purpose of Profitability Analysis? Is it to inform, or is it to demonstrate profitability?

The kind of analysis performed depends on whether it is factual or supporting decisions.

For the first type, factual, the analysis is designed to report the profitability status at a single point in time and can be standardised and automated. For the second type, decision support, analysis involves future profit projections, sometimes including full lifecycle modelling.

Decisions requiring deeper Profitability Analysis include whether to outsource or use in-house production and whether to keep investing, reduce or stop investing.

The Definition of Profitability

There are many definitions of profit. Some of the most common are:

- Variable profit = Revenues less direct costs

- Gross profit = Revenues less costs to deliver to a customer

- Operating profit = Gross profit less overheads

- EBIT = Profit less interest and tax

- Net profit = Profit after interest and tax – this is the bottom line of a business

To determine which definition to use, you need to be well acquainted with the concept of profit contribution. Profit analysis at a net profit level makes little sense usually. Taxes and financing expenses tend to be product, customer, and channel agnostic. Therefore, it is critical to define the relevant profit contribution for each of the four types of Profitability Analysis. The profit contribution concept states that the profit attributable can be reasonably measured and accounted for.

Allocation Mechanisms for Profitability Analysis

Revenue allocations are fairly straightforward to apply across the four types, as these are normally determined by the invoice. However, there can be potential allocation issues that need to be considered carefully. For example, if year-end customer bonuses decrease the revenue already recorded, they would have to be set up in the accounting system and allocated across those customers’ products. Credit notes and pricing corrections also create allocation issues depending on how these are recorded.

Cost allocations can be more complicated. Direct costs are straightforward, yet inventory write-offs can be tricky to allocate to a particular product or customer base. Logistics costs, including warehouse and shipping costs, can be difficult to classify depending on the complexity of the product mix. Many businesses use a concept called activity-based costing that allocates relevant costs, using granular activity drivers, across their product mix, customer base or channel split.

Most questions arise, however, in overhead costs, which are more commonly known as sales, general and administrative expenses (SG&A). If SG&A costs are organised by the market or by channel, it can be easy to allocate. Certain departments, such as customer service, are more problematic as they may support multiple channels, products, and customers. The same may hold true for support departments such as finance and HR.

The Importance of Master Data and Accounting Policies

This brings us to consider how sophisticated an allocation mechanism needs to be for Profitability Analysis. If an organisation does not manage its product, customer and material master data well, then questions about the analysis’s accuracy, consistency and robustness will be raised. It is important to note that allocation routines typically need to be set up outside the accounting system. While modern ERP systems can accommodate this within profitability modules, they need to be constantly maintained. It is especially true in organisations with constant profit and cost centre structure changes. Therefore, the sophistication of the analysis design should be driven by the purpose of the analysis.

When it comes to internal and external benchmarking, we need to consider the impact of the accounting policies employed. For example, the profitability of a product can be quite different depending on the inventory valuation method used. Applying the first-in-first-out (FIFO) method rather than the last-in-first-out (LIFO) method can significantly change the profitability outcome. Furthermore, suppose the depreciation of tangible assets is included in the product Profitability Analysis. In that case, any changes in the depreciation policy will need to be understood and should allow us to interpret the trends completely. Be aware of accounting policy changes that will impact revenue and cost recognition within your Profitability Analysis.

Profitability Analysis: The Cash Flow Perspective

Significant systemic shocks to the system, like the 2008 financial crisis or the COVID-19 pandemic, can lead to insufficient cash flow for daily operations and business insolvency.

It is important to note that, in the long term, net profit should equal the cash flow generated by the business. However, this may not be true at any particular point due to many accounting-related elements.

Does the risk of insolvency mean we should look at the cash flow for all four types of Profitability Analysis? Cash flow analysis makes sense at a customer level. A customer is obliged to pay for the goods or services they have received. However, if the customer does not pay, the business will record a profitable sale at first but later record it as a loss. In the end, all the company has on record is the cash spent providing those goods or services but no payment for it.

Cash flow analysis makes less sense at a product level. Any product does not influence the customer’s payment behaviour. They do not care about paying for individual products separately if they buy multiple products per visit. The only exception to these rules is in a project environment where one product or service equals one customer, and that customer is invoiced.

In Summary

This article has illustrated the importance of aligning the type of Profitability Analysis with the requirements of the individual situation. It also explains what definition of Profitability Analysis is the most appropriate one. For an effective Profitability Analysis, FP&A professionals need to be aware of potential allocation issues and consider them carefully. It is important to note that while cash flow analysis can be a useful addition to Profitability Analysis, it is not always the case.

This article was first published in the SAP Blog.

Subscribe to

FP&A Trends Digest

We will regularly update you on the latest trends and developments in FP&A. Take the opportunity to have articles written by finance thought leaders delivered directly to your inbox; watch compelling webinars; connect with like-minded professionals; and become a part of our global community.