In this blog, we will look at integrated Financial Planning and Analysis: what it is and...

Only two mechanisms influence a company’s future performance: decisions and luck. According to McKinsey, only 20% of organisations excel in decision-making, which means that the odds are that there is a massive performance improvement opportunity for your organisation.

What Is The Problem We’re Solving?

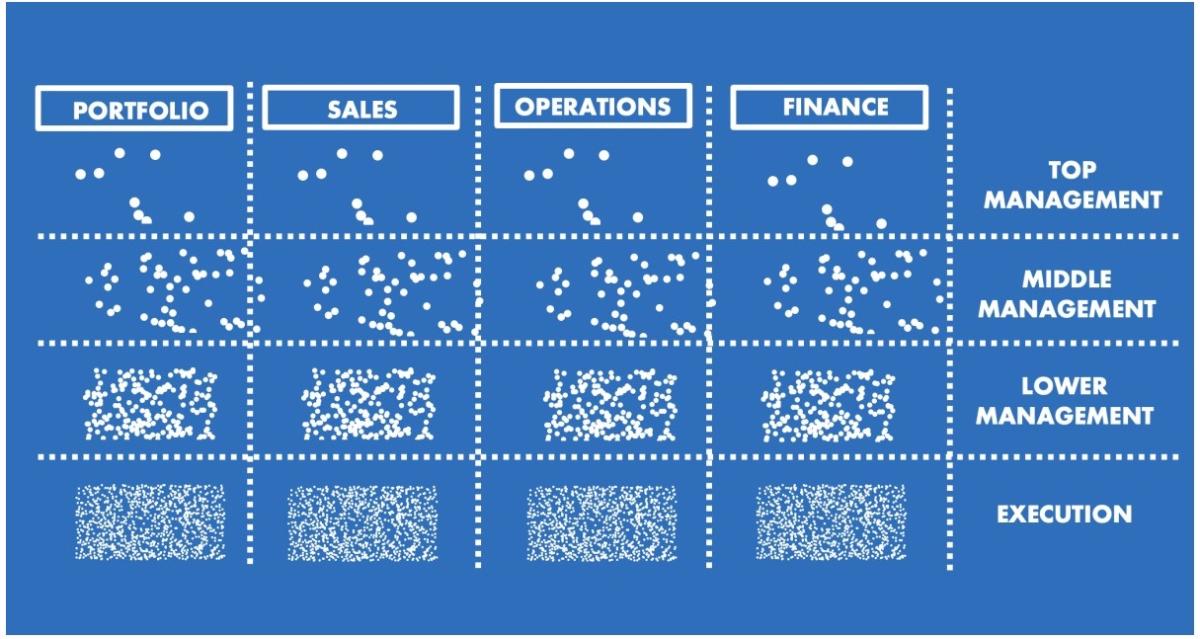

Most organisations are structurally silos. Functional and hierarchical boundaries divide decision-making into isolated parts despite the obvious cross-functional dependencies.

Planning processes are ways to break down these silos, but top-down and bottom-up approaches are often disconnected.

Figure 1: Organisations are structurally silos.

For example, Strategic Planning is often a plan-creation process, not a decision-making process. Indeed, only 11% of executives believe it’s worth the effort that goes into it. A company might list things it would like to do, develop the product portfolio, start a new talent program, etc., but it might not decide to develop new products or start a new talent program. This means there is nothing concrete to connect to on the next decision-making level; operational plans don’t include the new products or the new talent program because there is no decision yet to invest in them.

The disconnection of top-down and bottom-up planning processes directly results in not making real decisions within them, which is why the functional and hierarchical silos remain disconnected.

Another example is annual budgeting. Companies make resource allocation decisions in their annual budget, but those decisions are not connected to real-life ones like:

- launching a new product development project,

- starting a 3 million brand-building program,

- raising prices by 5%,

- or hiring 250 new people to work at the factory.

Companies make resource reservations that they might do those things in the future. But what if the decision (assumption of a decision, really) to hire 250 people is based on the assumption that the market will grow 10%, and in reality, it falls by 10%? Is the company still going to hire those people? Of course not. It’s going to re-evaluate and make that decision with a mechanism other than budgeting. But for some reason, it often still hangs on the plan (budget), which is no longer based on reality.

Planning cadence in annual budgeting is not connected to real-world decisions. For example, the list of major real-life decisions that it is best to make in autumn for the next calendar year is as long as the list of Swedish war heroes, i.e., non-existent. This makes for a theoretical plan creation process rather than an effective and efficient planning (i.e., decision-making) process.

Because organisations make real-life decisions somewhere other than in their planning processes, these processes often remain theoretical plan creation (or forecasting) ones, disconnected from each other and reality.

Strategy and Execution

Strategy is a clear set of integrated choices (decisions) as to where the company is going to play, how it’s going to win, what its capabilities are, etc. Strategy is about the entire organisation, not about any individual part of it. Its purpose is to create a focus for the whole, i.e., deciding to do some things and not to do others. These choices must be easy to understand.

Execution is at the lowest level in the decision-making hierarchy, while strategy is at the highest level. For instance, a salesperson visiting a customer or a factory worker building a tire on a tire-building machine are examples of execution-level decisions.

Decisions at an execution level are dependent on vertically higher-level choices (for example, customer classification or choices of customer segments). They may have horizontal interdependencies (for instance, a salesperson visiting a customer will impact orders received at customer service). Still, they do not set new dependencies for other hierarchically lower-level choices that someone else would make later.

How to Connect Strategy and Execution?

Simple answer: stop making plans and start making decisions.

We have seen that strategy is the integrated set of the biggest decisions about the whole. Execution decisions are the smallest individual decisions scattered all over the organisation. In between reside structural organisational silos, which can hinder the alignment and connection of the two. The problem to solve is to find the most effective and efficient way to connect the cross-functionally interdependent decisions in the different silos.

According to McKinsey, the answer is to run a process. It is the number one predictor of decision quality for cross-functional decisions. Moreover, it’s 6 times more important than analysis in creating business benefits like growth, profitability, productivity and gaining market share.

Connecting strategy to execution is about connecting the top-down planning processes to the bottom-up planning processes. In this context, planning refers to decision-making, not plan creation. The best definition of planning is by Alan Lakein:

“Planning is bringing the future into the present, so you can do something about it now”.

Planning is about influencing the future, not about creating plans or forecasts. Yes, planning entails both, but neither is its purpose. Improving decisions is.

The first criterion for connecting strategy to execution is clear strategic choices. For example, premium winter tires to aftermarket, instead of economy summer tires to OEMs. Those are big where-to-play decisions because they define the boundaries of all other decisions in the organisation.

According to McKinsey, only 30% of companies make clear choices in their strategy, which means that for most, there is nothing to connect to on the next-level decisions from “Strategic Planning”.

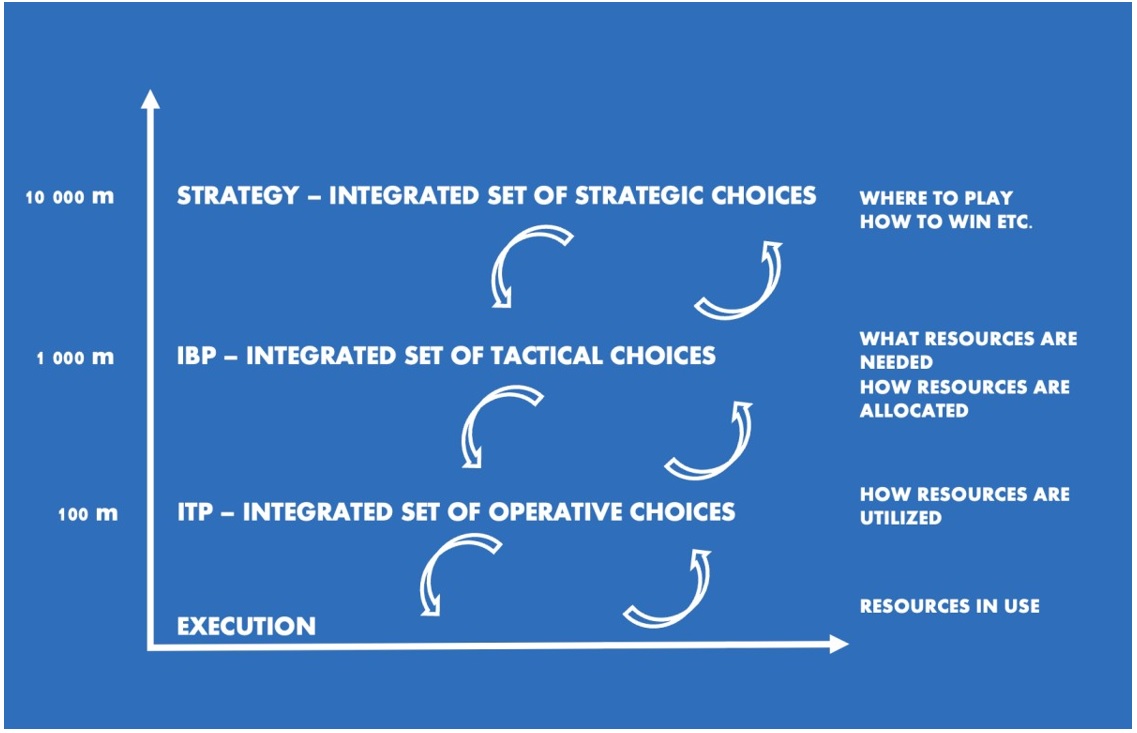

Figure 2: Levels of decision-making.

The second criterion is to run cross-functional decision-making processes: one on a tactical level and one on an operational level.

Why two? Because of the types of decisions.

On a tactical level, most decisions are about resourcing: to increase, decrease or reallocate resources based on genuine business decisions. For example, how many millions should be invested in the marketing of each segment, how many people to hire for R&D, which product lines to invest in, how much inventory to build, etc.

An analogy could be budgeting without the political nonsense often dominating the annual process.

The solution is to run a monthly process that looks 24 – 36 months into the future. Why monthly? Because companies make resourcing decisions continuously, not annually. Why 24 – 36 months? Because real-life resource commitments often go that far out in the future. The cadence and time horizon are based on real-life decisions, not artificial constraints.

On an operational level, decisions are about how to utilise the existing constrained resources best. In the short term, an organisation cannot hire 100 new people for sales. However, it can decide which customers current sales managers will visit, which products they will focus on selling, and how all that aligns with the new products in the pipeline and with the capacities and inventories committed to in supply.

Decisions on an operational level are more urgent, and commitment to them is shorter. These are the reasons to run the process on a weekly cadence focusing on a shorter time horizon (where the organisation is constrained by its resources).

Summary

Organisations are structurally silos. Planning processes are the most effective and efficient way to break those silos. Traditional planning processes (like Strategic Planning or annual budgeting) are often disconnected from other planning processes and execution because they are not decision-making processes but theoretical plan-creation processes.

The solution is to run cross-functional planning (decision-making) processes on a tactical and operational level, connecting the clear, integrated set of strategic choices to the millions of smaller decisions made daily in execution.

References:

- AMINOV, Iskandar, DE SMET, Aaron, JOST, Gregor, MENDELSOHN, David. “Decision-making in the age of uncertainty.” McKinsey. April 30, 2019. https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/people-and-organizational-performance/our-insights/decision-making-in-the-age-of-urgency

- LAFLEY, Alan George, MARTIN, Roger. “Playing to Win: How Strategy Really Works.” Harvard Business Review. December 18, 2014. https://hbr.org/2014/12/playing-to-win-how-strategy-really-works

- BRADLEY, Chris, MATSON, Eric. “Putting Strategies to the Test.” McKinsey. January 1, 2011. https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/strategy-and-corporate-finance/our-insights/putting-strategies-to-the-test-mckinsey-global-survey-results

- MANKINS, Michael, STEELE, Richard. “Stop Making Plans; Start Making Decisions.” Harvard Business Review. January 2006. https://hbr.org/2006/01/stop-making-plans-start-making-decisions

- LOVALLO, Den, SIBONY, Olivier. “The Case for Behavioral Strategy.” McKinsey. March 1, 2010. https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/strategy-and-corporate-finance/our-insights/the-case-for-behavioral-strategy

Subscribe to

FP&A Trends Digest

We will regularly update you on the latest trends and developments in FP&A. Take the opportunity to have articles written by finance thought leaders delivered directly to your inbox; watch compelling webinars; connect with like-minded professionals; and become a part of our global community.