In this article, we will look at how driver-based advanced analytics has overcome the problems with...

This is the second article in a series of articles devoted to the wide variety of the benefits provided by the next generation budget, the operational budget (OB), and its associated operational income statement (OIS). This article will describe OB’s benefits over the current budgeting process and its results. It will be of particular interest to FP&A professionals focused on the current budgeting process and how to improve it.

This is the second article in a series of articles devoted to the wide variety of the benefits provided by the next generation budget, the operational budget (OB), and its associated operational income statement (OIS). This article will describe OB’s benefits over the current budgeting process and its results. It will be of particular interest to FP&A professionals focused on the current budgeting process and how to improve it.

This article has three sections: i) a comparison of the two budgets’ processes, ii) the problems with the traditional budget process and the benefits OB provides to address them and iii) conclusion including future articles.

The first article described how predictive and prescriptive analytics make OB possible and how easy it is to demonstrate OB’s value for a firm. NOTE: If the reader is unfamiliar with the first article, OB’s benefits described in this and subsequent articles will not be fully appreciated.

Elaborating on the OB’s advanced analytics, while predictive analytics have been popular for years, prescriptive analytics have been embraced more slowly. Fortunately, according to Gartner, prescriptive analytics is at a tipping point. Specifically, quoting from their report titled "Snapshot for Prescriptive Analytics, worldwide, 2019: "Currently, 11% of large and midsize organizations have some form of prescriptive analytics; this will grow to 37% by 2022." (bold added)

Comparison of the Two Budgets’ Processes

Traditional budget

Today's traditional budgeted income statement starts with the budget being developed jointly by Finance and the departments of the line organization. Specifically, next year’s forecast along with all the assumptions appropriate to next year’s budget (e.g., new products, out/in sourcing decisions, changes in suppliers, manufacturing process improvements including CAPEX investments) are sent to departments’ managers. They, in turn, create the departmental cost inputs to the budget for review by Finance. After a negotiation process, the results are then entered into the Chart of Accounts (CoA) which reflects the firm’s organizational structure.

Thus, the budget’s cost inputs are disparate because they either have different drivers or no drivers at all. As such, the traditional budget can’t be modeled prescriptively. Also, it can’t be modeled predictively (i.e., a flexible budget, see below) if any of the departments’ cost inputs have no driver.

The budget developed is typically referred to as a static budget. It does not change even if the underlying activity level of the business differs during the budget period from the level assumed when the budget was constructed.

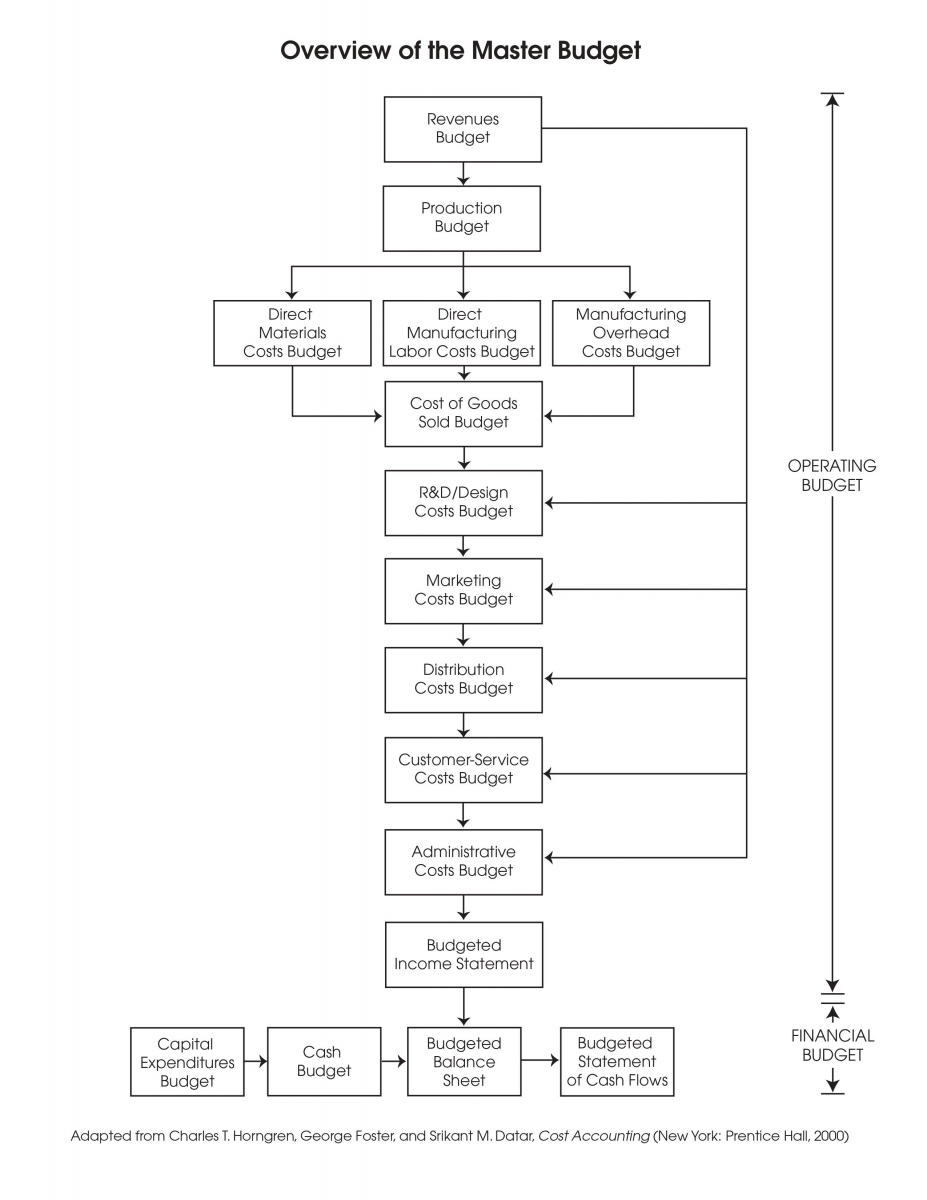

This traditional budgeting process flow is charted in Horngren’s et al Cost Accounting, Chapter 6, "Master Budget and Responsibility Accounting". See Figure 1 below.

Figure 1. Overview of the Master Budget

A static budget differs from a flexible budget. A flexible budget creates a model that predictively calculates different expenditure levels for variable costs, depending upon changes in the amount of actual revenue or other activity measures (i.e., drivers). Thus, variances are the result of actual expenses that have been normalized for actual revenues and related actual activities.

Operational Budget (OB)

(a) An activity-based baseline OB model of last year’s p/l is created and its results compared with last year’s actual results; the objective is to be within 2%. The underlying rationale is simple: if history can be reasonably replicated, then the willingness to accept recommendations about the future increases.

As described in the first article, only activities with a variable cost component are included in the model as activities that are 100% fixed have no impact on the model’s solution.

Activity-based drivers allow a prescriptive model to be created of the budget. This is the same prescriptive modeling technique that has been used for supply chain network design for decades.

(b) Next year’s forecast along with all the assumptions appropriate to next year’s budget are entered into the baseline model.

(c) In addition, response functions are added to the baseline model. These describe how the forecast varies as a function of sales and marketing expenses. Thus, the OB will have a different and more profitable forecast than the one entered in (b), above.

(d) Since the OB develops a new forecast, there is no way of knowing, a priori, what the product volumes will be. Thus, where feasible, all the activities, plants and links for all time periods are appropriately capacitated. Further, when there is more than one option (e.g., second shift, outsource, build ahead, over time), they all should be included so the best one is chosen.

Also, included are, when applicable, constraints. Examples include customer service, raw material suppliers, DC locations (throughput and inventory), energy or carbon implications, transportation links and procurement availability limits.

(e) Finally, the updated baseline model is solved and the OB is the solution.

It is important to understand that the process described above is only required for the first OB model. For the operational budgets that follow, all that’s required is (b) and (e) above.

Also, a simpler version of this process is all that’s required to demonstrate easily the OB’s budget value proposition for the firm; specifically, steps (a), (c) (d) and (e). Then subtract the profit in (e) from last year’s profit to determine how much profit last year’s budget process left on the floor.

Problems with the Traditional Budgeting Process and How OB Addresses Them

Since Horngren et al do not describe the process of creating the traditional static budget in sufficient detail, the author turned to another resource, Bragg’s Budgeting, the Comprehensive Guide, third edition.

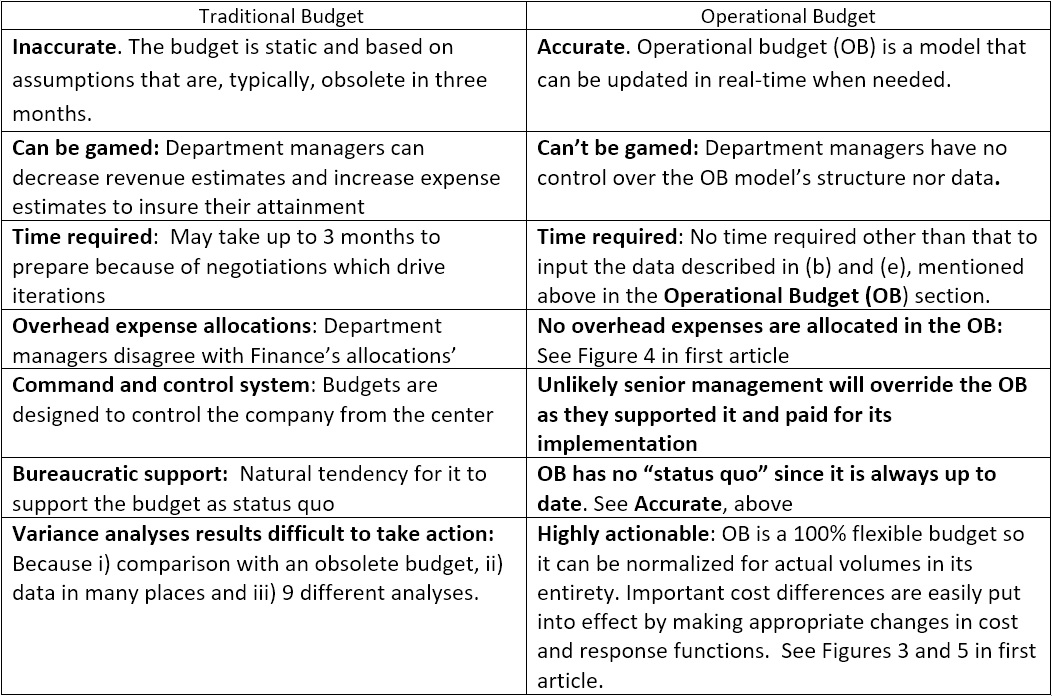

The following 6 issues with the static annual budgeting process are taken from Bragg’s book, paraphrased. How OB addresses these issues is shown in Table 1 below.

A seventh problem was added, variance analysis, because Steve Morlidge, a frequent FP&A Trend contributor and a budgeting expert, in his 2010 book Future Ready co-authored with Steve Player, commented on page 240 that “Variance analysis should be eliminated.” (NOTE: As described in Bragg’s book, the principle advantage of flexible budgets is the ease of performing the variance analysis, itself, and the analysis’ ease of being enacted.)

Morlidge went on to publish a four-part working paper titled “Beyond Variance Analysis” in 2016 which very thoroughly details variance analysis alternatives. The paper concluded: “The end result will be a more nuanced, thoughtful and insightful analysis of the state of organisational affairs, beyond variance analysis.”

Table 1

Conclusion

Table 1 is the conclusion to this article as it illustrates the power of the OB to address FP&A and CFO’s current headaches with the traditional budget.

The next three articles will describe efforts, previous to the OB, to improve the current budgeting process.

The first is the rolling forecast; the second is eliminating the budget altogether by implementing the six leadership principles and six management processes of the Beyond Budgeting Institute and the third is Zero Based Budgeting.

Following those two articles will be two articles describing benefits for two functions outside Finance and a cross-functional application. The first will be S&OP/manufacturing and the second sales/marketing’s ROI and the cross-functional application is scenario planning.

Then, an article describing an illustrative OB test case; it will show how well OB actually works.

The concluding article will describe how OB’s analytics can be applied to extend M&A’s current advanced analytics.

Subscribe to

FP&A Trends Digest

We will regularly update you on the latest trends and developments in FP&A. Take the opportunity to have articles written by finance thought leaders delivered directly to your inbox; watch compelling webinars; connect with like-minded professionals; and become a part of our global community.