Over the twenty years that I have worked with Beyond Budgeting, I have asked tens of...

Although Beyond Budgeting is about so much more than just budgets, our name tends to draw people, at least initially, towards the budget word. Once there, cost management often pops up as the number one issue, for obvious reasons. How can we manage cost without a budget? Cost management (or resource allocation) is however only one of twelve principles, although the topic is indirectly addressed in other principles like Values, Transparency, Autonomy and Rhythm.

Although Beyond Budgeting is about so much more than just budgets, our name tends to draw people, at least initially, towards the budget word. Once there, cost management often pops up as the number one issue, for obvious reasons. How can we manage cost without a budget? Cost management (or resource allocation) is however only one of twelve principles, although the topic is indirectly addressed in other principles like Values, Transparency, Autonomy and Rhythm.

There are many other great concepts and communities out there which also challenge traditional management: Lean, Agile, Sociocracy and Holacracy, to mention a few. We all fight the same enemy. None of them, however, have, to my knowledge, any clear recommendations about how to manage cost in different and better ways than through the traditional, detailed and annual budget. Although this area might be regarded as “Finance stuff”, it is too important to be ignored. There is hardly any part of the management model that affects a manager more decisively than a budget. Everyone is given one. For a large majority that means a cost budget; how much can you spend next year, and on what. Everyone knows the game and consequences of not obeying the rules.

For a company embarking on a radical change journey, there is hardly a more effective place to start. Making tangible and positive changes to budget cost management is a very effective way of signalling real change. It affects all managers, instantly and concretely.

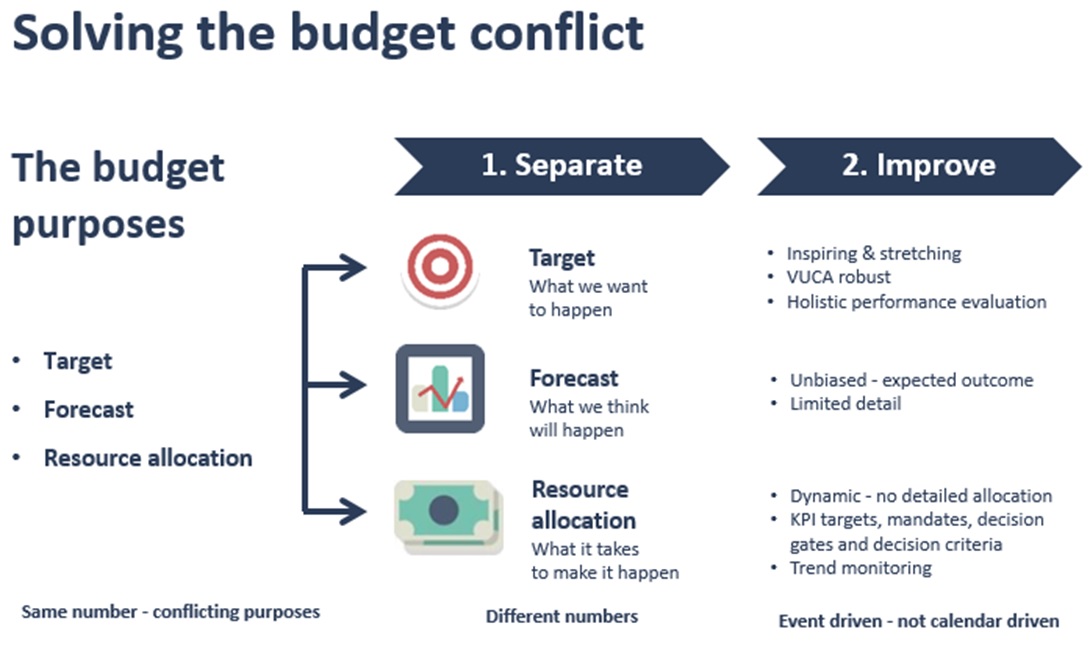

We always recommend starting with the separation of the three budget purposes target setting, forecasting and resource allocation before any improvement work is done on any of the three. The reason is the troublesome conflicts between these three purposes. Read more in the previous blog “The Rolling Forecasting trap”.

The separation enables significant improvement of each purpose, as they now are handled in separate processes.

The Beyond Budgeting principles, as well as practices developed by companies on the journey, provide a wide range of tested and tangible alternatives, including for traditional budget cost management, or resource allocation.

Here is what we do at Statoil. Please note that this is our way, and not the way. Others have found other ways, some much simpler than what we do in Statoil. I will share a few examples at the end.

Statoil is in the very capital-intensive energy business. We are typically investing between 10 and 20 billon USD dollars annually. Despite the big money involved, for our capital projects it’s not that difficult. Although we lately have had some self-imposed constraints on our overall investment level, there is no annual, detailed investment budget with all decisions made in the autumn. Instead, “the bank is always open”. The line can forward projects for approval at any time. How high up one needs to go is regulated by a mandate structure, which needs to be generous enough to avoid too many decisions ending up in the Executive Committee. Yes or no to a project depends on two things only:

- How good is the project? (strategically, financially, non-financially)

- Do we have the capacity? (financially, organisationally - as things looks today)

We use dynamic forecasting to monitor that new commitments are within our constraints – which also is a dynamic picture.

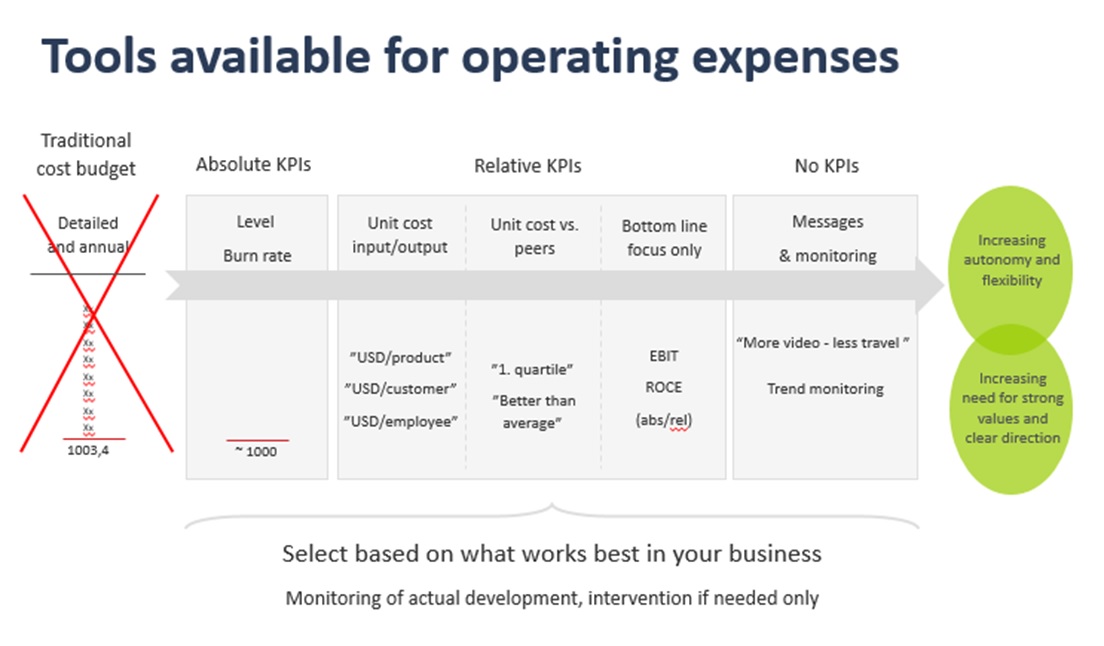

Managing operating cost without a budget is more challenging, but absolutely possible. Here, there are fewer big and distinct decision points, so we need other mechanisms, as illustrated below:

What we leave behind is the detailed, annual budget, as described on the left. Too detailed, too early and often “too high up” decision making.

Instead, we offer a menu of alternative mechanisms for the business to manage its own costs. These include a “burn rate” guidance ("operate with full autonomy within this approximate activity level"), unit cost targets (“you can spend more if you produce more”), benchmarked targets (“e.g. unit cost below average of peers”), profit targets (“spend so that you maximise your bottom line) or simply no target at all (“we’ll monitor cost trends and intervene only if necessary").

The further to the right we move on this menu, the more trust is shown. There is just one thing we know for certain with trust: someone will abuse it. At Statoil, it has happened, and it will happen again. The simple but wrong response is to put everyone in jail because someone did something wrong. The right response is to deal firmly with those involved, and let it have the necessary consequences. This is not about being soft and evasive.

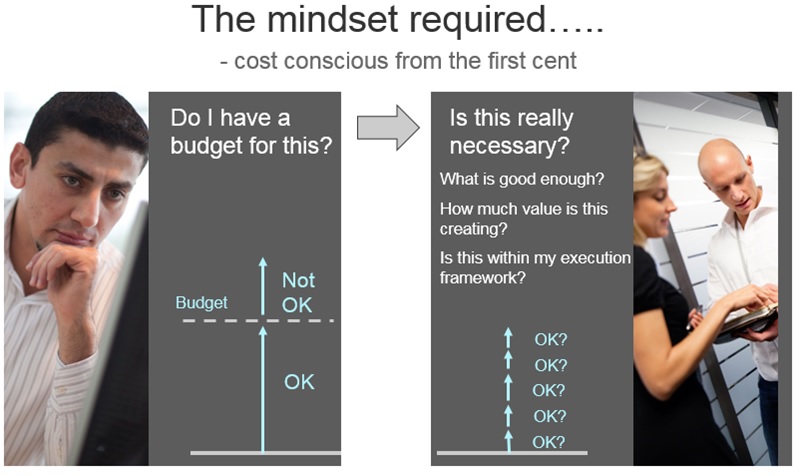

These mechanisms need to sit on top of what we call a “cost-conscious mindset”, but they can also stimulate and develop such a mindset. Management processes drive culture, to the better or to the worse. The mindset we are after implies asking different questions when a decision with cost implications is made:

Let me finish with two examples from other companies. They have both built a mindset and a culture so strong that they hardly need anything in addition.

The Beyond Budgeting pioneer Handelsbanken has operated without budgets for almost fifty years. Cost control is achieved through autonomy and transparency. Branches are benchmarked on the KPIs Return on Equity, Cost/Income Ratio and Customer Satisfaction. It’s all visible, and nobody likes to be laggards. The branches have full autonomy to apply the right doses of cost to optimise their performance on these three KPIs. Very simple, very self-regulating. And very effective. Handelsbanken is the most cost-effective universal bank in Europe.

The Norwegian IT company Miles never had a budget. Employees can buy whatever PC they want, as expensive as they want, and replace it as often as they want. They can attend any course or conference, wherever in the world, as often as they want. Miles only require one thing; you have to post on the intranet what you bought or what you did, and the cost of it.

And their only small concern about using transparency as the only control mechanism? Could it be too effective…?

The article was first published in Unit 4 Prevero Blog

Subscribe to

FP&A Trends Digest

We will regularly update you on the latest trends and developments in FP&A. Take the opportunity to have articles written by finance thought leaders delivered directly to your inbox; watch compelling webinars; connect with like-minded professionals; and become a part of our global community.