The Logical Thinking Process was originally developed by Dr. Eliyahu M. Goldratt, author of bestselling business...

The daily routine of FP&A professionals revolves around providing reports and analyses for senior and operational management, to manage core processes such as budgeting, forecasting, cost allocation and consolidation. And usually, they are hard-pressed for time.

The daily routine of FP&A professionals revolves around providing reports and analyses for senior and operational management, to manage core processes such as budgeting, forecasting, cost allocation and consolidation. And usually, they are hard-pressed for time.

At the same time, the key complaint from senior and operational management is that the finance professionals really don't understand the business well enough. That is the people who should be at the forefront of providing insights to support top-quality decision-making lack the understanding required to perform this task. That is a serious issue.

The Challenge of Business Partnering

Ambitious finance people want to be business partners, not just support functionaries. They take time to gain a better understanding of the business, they network with colleagues outside finance, they seek out experienced co-workers in order to learn from them. Some even use their spare time to analyse the business to better understand it.

The concept of finance business partnering reflects the realization that finance professionals could and should add more value, and that value eventually could and should be based on a better understanding of the business. There is a strong drive visible here, lots of discussions, articles, books and interesting endeavors. But unfortunately too little has changed.

Finding the Root Cause

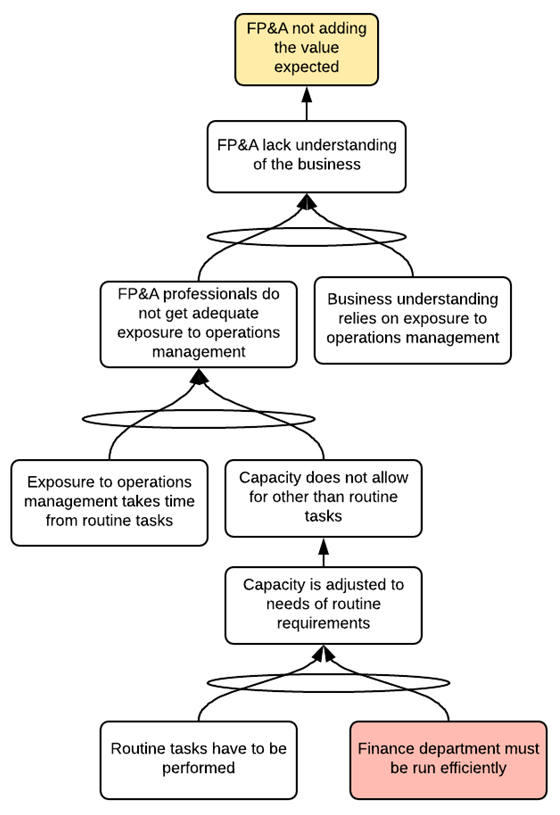

Why is that? The first step is to try and figure out why managers complain about the value finance professionals bring to the table. In this analysis, I use a Current Reality Tree, one of the five tools of a highly effective methodology called the Logical Thinking Process. The purpose of the Current Reality Tree is to identify the root cause of a problem, using sufficiency logic.

We know the complaint: FP&A professionals don't create enough value. When we ask why the answer is they lack an adequate understanding of the business. Too little real exposure to the challenges of operations explains lack of business understanding. Time and capacity are the constraints and at the root lies the focus on departmental efficiency that, as many of us know from experience, plays such a large part in the way we structure and manage our businesses.

Note this is a generic example. The analysis may well vary between different companies. Sometimes it may reveal a vicious cycle, for example when a rigid annual budgeting process drives sandbagging, which then must be justified by an ever-growing number of unnecessary, but efficiently performed tasks.

Diagram 1: Generic Current Reality Tree for FP&A – Example.

The Efficiency Mantra

Preparing reports, building budget templates, responding to demands for analyses are all technical activities. Networking, reading or just walking around the factory in order to better understand the business you work for are not technical activities. It is very difficult to measure efficiency when doing this while it is easy to measure efficiency at pulling together a report. And we like to measure performance.

If you spend a day fine-tuning a cost allocation template no questions will be asked. But if you spend a day in the warehouse, trying to better understand processes and procedures, people are likely to give you a funny look when you get back to the office. No matter if the allocation is not really used for any decisions, while your experience in the warehouse allows you to bring really valuable input that improves decision making.

Since time is usually scarce, finance people try to find ways to increase efficiency in their department. Apart from basic accounting systems, businesses invest in special applications for reporting, planning and budgeting, cost allocation and consolidation in order to speed up those processes. Analytical applications are widely used for the purpose of improving and, up to a point, automating data analysis and variance reporting.

All of this is meant to improve the efficiency of the finance departments. Reports and budgets are churned out quicker, consolidation and cost allocation are automated, all to save work and minimize the risk of errors.

Doing the Right Things or Doing Things Right?

But what about value? Does faster report generation make the reports better, provide more valuable insights, help managers make better decisions? Or does it simply lead to more reports, with more details, being generated? Does a better budgeting system make the budget a better management tool, more up to date, more relevant in decision making, or does it just lead to a more elaborate, less relevant budgets? Based on my own experience providing planning and budgeting solutions for almost 20 years, this is unfortunately what happens far too often.

Higher efficiency does not necessarily increase effectiveness. Doing something faster, with more precision, fewer resources or more often adds no value at all unless the thing we are doing is in itself something that adds value. If not, no matter how fast or often we do it, it will just be a waste of time. Efficiency by itself adds no value, effectiveness does.

We like to measure performance. But effectiveness is not always that easy to measure. If walking around the factory for a few days makes you a more effective FP&A professional, how is this going to be measured? It is not easy. There is no direct verifiable link between the time you spend in the factory and the quality of the insights you provide once you have done this. And there is not even any proof that the better quality of your insights will necessarily lead to better decision making by those who benefit from them. This is not even under your control. In other words, we know a more knowledgeable FP&A professional will add more value. But we cannot really measure it while we can measure how fast they perform a task that in fact adds no value. And we like to measure performance. It is in fact what an FP&A professional does for a living! But measurements can be a two-edged sword as we will see in the second part of this discussion.

Subscribe to

FP&A Trends Digest

We will regularly update you on the latest trends and developments in FP&A. Take the opportunity to have articles written by finance thought leaders delivered directly to your inbox; watch compelling webinars; connect with like-minded professionals; and become a part of our global community.