The daily routine of FP&A professionals revolves around providing reports and analyses for senior and operational...

In the first part of this discussion, we identified the root cause that prevents FP&A to deliver its full value. In fact, we have identified a core conflict of FP&A. This conflict can be described in different ways.

In the first part of this discussion, we identified the root cause that prevents FP&A to deliver its full value. In fact, we have identified a core conflict of FP&A. This conflict can be described in different ways.

We can talk about a conflict between effectiveness and efficiency. We can also talk about it as a conflict between local and global optima - between focusing on the system as a whole and focusing on parts of the system. In this context, we can also talk about functional silos. And in many cases, this tension becomes visible as a conflict between the traditional command-and-control management approach and trusting people to do their best of their own free will.

When we have a long-standing problem we have repeatedly tried to solve without success, chances are behind the problem there is a conflict preventing us from reaching a solution. To get rid of the problem we have to solve the conflict.

The Logical Thinking Process methodology offers an excellent tool that can help us unravel conflicts like this. It is called a Conflict Resolution Diagram, CRL. Like the other steps in the Logical Thinking Process, the CRL, demands precision: it requires that we first state precisely where the conflict lies. The CRL applies only to conflicts where there is a common objective but two conflicting ways to achieve it. The diagram usually contains five entities: The common objectives, two requirements, both needed to fulfill the objective, but which in turn have two opposing prerequisites.

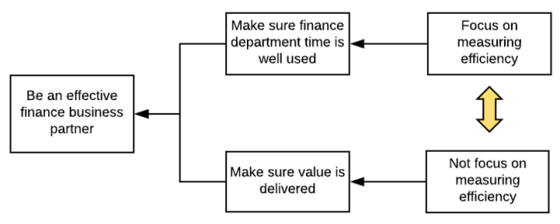

Using a Conflict Resolution Diagram, our conflict may look something like this:

Diagram 2: The Core Conflict

We read the Conflict Resolution Diagram from left to right, linking the statements using necessity relationships: IN ORDER TO be an effective finance business partner I MUST make sure my time is well used AND I MUST make sure I deliver value. If either of those requirements is missing I will not be effective. Then, IN ORDER TO make sure time is well used I MUST focus on measuring efficiency. But, at the same time, IN ORDER TO make sure value is delivered I MUST NOT focus on measuring efficiency. In other words, we must do X and we must also do the opposite of X. Two objectives we have to fulfill and they are in contradiction to each other. This is why we have a conflict.

What are the assumptions?

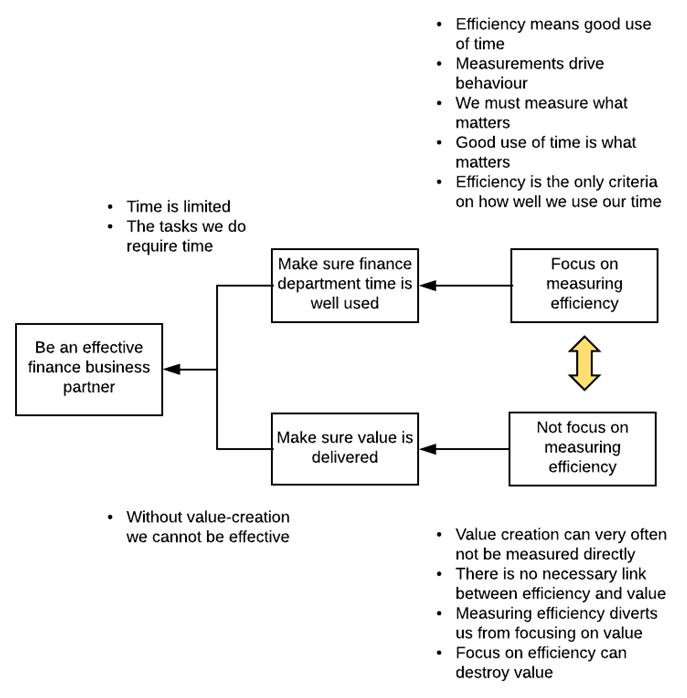

What lies behind this conflict are assumptions I have already brought up. Let's add those into the diagram:

Diagram 3: Assumptions behind the Core Conflict

Now we see clearly what lies behind the logical relationships. The next step then is to scrutinize those assumptions. Let's start from the left. To be effective we must use our time well because time is limited and what we are doing takes time. Valid? In most circumstances, we can assume it is. We can usually not expect to have overcapacity in the finance department, and it goes without saying really that anything we do will take some time. So the relationship is valid.

Let's look at the lower arrow now: To be effective we must deliver value. This is really the definition of effectiveness so it goes without saying. Hence the requirements for being an effective business partner both seem to be valid: We must make the best use of our time and we must make sure we deliver value.

But what about the prerequisites? Let's look at those now. The first prerequisite is that in order to use our time well we must measure efficiency. The first assumption looks pretty tight. Efficiency is about good use of time – the less time and resources we use the more efficient we are. Secondly, we know that we act based on how we are measured and if efficiency is what matters then we must measure that to maximize it. Looks pretty tight also. Finally, if measuring efficiency really is a prerequisite for using our time well we actually must assume that efficiency is critical to good use of time. That is, without efficiency time is not well spent. Otherwise, measuring it would not be a necessity.

On the lower half, we have the opposite. If we want to make sure we deliver value we should NOT focus on measuring efficiency, and there are four reasons: First, we assume that value creation can often not be measured at all. Secondly, we assume there is no necessary link between efficiency and value - i.e. we can be highly efficient, but not create any value. Third, we assume that a strong focus on efficiency will divert us from focusing on value. Fourth, in some cases, we can even assume that the drive for efficiency directly destroys value. This will happen for example as a result of measurements that are aimed at improving local optima at the cost of global optima.

Are any of the assumptions invalid?

How valid are those assumptions? The first one relates to the way operational experience enables an FP&A professional to bring valuable insights. There is however no direct relationship between the time spent on the shop floor and the value of the business understanding this brings. It is impossible to measure directly. Still, we know it does bring value.

The second assumption more or less goes without saying: You can be very efficient at doing non-value-adding stuff. Those two assumptions are sufficient to conclude that measuring efficiency is not enough, but they do not suffice to conclude we absolutely should not measure it.

In order to reach that conclusion, we must bring up an adverse effect – that measuring efficiency is not only useless but actually harmful. This is the third assumption, that focusing on measuring departmental efficiency actually diverts us from focusing on value to the company as a whole. And this is the root of the contradiction.

Now let's think again about the difference between efficiency and effectiveness. What were the key points?

- Efficiency by itself brings no value.

- Effectiveness brings value.

- We can at the same time be highly efficient and totally ineffective.

- Efficiency is easy to measure while effectiveness can be hard to measure.

Based on the first two points we can conclude that effectiveness must come before efficiency. Efficiency becomes relevant only after we have made sure what we are doing is actually effective. It follows that efficiency cannot possibly be the only criteria on how well we use our time. This again means there really is no necessary relationship between good use of time and focus on efficiency.

The other issue here is the difference between departmental performance and global performance. The efficiency we measure is the efficiency of the finance department. But a highly efficient department can easily be totally ineffective at delivering value into global decision making.

FP&A has the potential to add much higher value than it currently does. The conflict between the drive for departmental efficiency and the demand for valuable business insights severely limits this value-creation potential.

We have found that one of the prerequisites, the one that has to do with efficiency, is in fact not a necessary logical requirement to reach the goal. But at the same time, the focus on efficiency and departmental performance is very deep-rooted in our corporate culture and it is not necessarily clear what should replace it. Therefore unearthing the logical flaw is only the first step towards solving the problem. More work is needed. But the key point is, for FP&A to live up to its full potential, the conflict will have to be solved.

Subscribe to

FP&A Trends Digest

We will regularly update you on the latest trends and developments in FP&A. Take the opportunity to have articles written by finance thought leaders delivered directly to your inbox; watch compelling webinars; connect with like-minded professionals; and become a part of our global community.