In this article, the author explains how AI is transforming FP&A from a reporting function into...

Looking back at my notes from late 2024 regarding expectations for 2025, the dominant theme was one of optimism, bordering on hype, about how quickly the world was expected to change. Much of that optimism centred on the anticipated release of GPT-5. At the time, many people described it as an AGI-level breakthrough and predicted widespread disruption, including mass layoffs.

Some of those predictions did materialise: layoffs did occur (the impact of Artificial Intelligence (AI) is questionable), and AI adoption accelerated in visible ways. But the broader AGI narrative overstated both the immediacy and the scope of change. What actually happened was more uneven, with a significant impact in certain roles and industries, alongside slower and more constrained progress elsewhere.

What 2025 Got Right About AI

In many ways, 2025 turned out to be a strong year. At the same time, it was unexpectedly noisy. Nearly every conversation became an AI conversation. Products that were previously well understood, such as ERP systems, planning platforms, and reporting tools, were suddenly repositioned as “AI-powered.” This applied to both established, large-scale ERP vendors and newer, AI-native tools.

The same pattern showed up in point solutions. Reconciliation, reporting, forecasting, and close tools were all rebranded around AI capabilities, while “solve-it-all” AI platforms like N8N.ai, ChatFin.ai began to emerge.

In practice, this created confusion rather than clarity.

FP&A teams struggled to understand which tools actually added value versus which were simply layered with AI features.

CFOs faced difficulty deciding what to buy and how to prioritise investments.

IT teams were left to sort out deployment, integration, and ownership without clear standards or governance.

As a result, 2025 became less about transformational outcomes and more about distinguishing between signal and noise. That said, there were still a few genuine silver linings in how the year ultimately unfolded, but they were more incremental and operational than the sweeping changes many had expected.

What 2025 got right is that AI became impossible to ignore. It moved quickly from a technical curiosity to a board-level topic. Boards, executive leadership, and finance leaders all began treating AI as a strategic priority rather than an optional experiment. CFOs actively directed their teams to explore how AI could be incorporated into finance processes, and many teams engaged in substantive discussions with vendors to understand both the possibilities and the constraints. Finance teams are now materially more informed about where AI can be applied, where it adds value, and where its limitations remain. Leaders now expect AI capabilities to be part of the core finance stack. AI is no longer a differentiator in tool evaluations; it is a baseline question raised in nearly every procurement discussion.

It is hard to recall another technology that entered boardrooms and leadership conversations this quickly. The proliferation of vendors, platforms, and AI-native tools also played a constructive role. While it added noise, it accelerated the learning process. Many finance leaders can now skip the early experimentation phase and focus directly on value creation, using prior market exploration and peer learnings to narrow where AI investment makes sense.

The Missed Transformation for FP&A

For FP&A teams, the outcome of 2025 was not a lack of AI exposure, but rather a lack of a clearer understanding of what actually moves the needle. The teams that made progress did so by making deliberate choices about ownership, process, and scope.

One practical shift was the question of ownership. AI initiatives that sat loosely between finance, IT, and analytics teams rarely moved beyond experimentation. Where FP&A leaders took direct ownership of specific use cases, such as forecast reviews, variance analysis, or management reporting, adoption was more durable.

Another important lesson was that process clarity mattered more than tool sophistication. Teams that began with a clear understanding of where time was lost, where judgment was repeatedly applied, or where reviews consistently stalled were better positioned to apply AI in a meaningful way. Teams that started with tool selection often struggled to connect AI features to actual FP&A workflows.

The larger miss in 2025 is that the transformational change many expected did not materialise. Despite widespread curiosity and discussion, AI budgets were often not allocated at a level that would support meaningful implementation. In several cases, teams were asked to explore AI tools without dedicated funding, which limited adoption to surface-level experimentation rather than operational change. This showed up clearly in areas such as predictive analytics and anomaly detection. These were frequently cited as high-value AI use cases for FP&A and finance operations; yet, relatively few teams implemented them in a production-grade manner. While many organisations reported “using AI” in their FP&A processes, usage was typically confined to general-purpose tools such as ChatGPT or Microsoft Copilot to speed up isolated tasks.

Adoption of those tools was easy, expectations were high, and many predicted it would meaningfully reshape finance workflows. In practice, its generic capabilities proved insufficient for deep finance use cases. After an initial enthusiasm, usage in FP&A plateaued. Teams began to question the depth, reliability, and repeatability, especially for analyses that required consistency from month to month.

The Persistent Data Problem

A core limitation is that finance and FP&A work spans multiple systems, processes, and exception-driven workflows. Standalone or generic AI tools do not operate across that full landscape. Without tight integration into core finance systems and without budget and ownership to support that integration, the impact of AI remains fragmented. In that sense, tooling, architecture, and investment discipline mattered far more than curiosity or intent.

There remains an unresolved foundational problem: data fragmentation. As finance teams began seriously evaluating AI, data issues consistently surfaced as the primary constraint. Data models and definitions still vary across systems, data remains distributed across multiple sources, and questions about accuracy and ownership persist. Teams continue to debate which system represents the source of truth, while master data inconsistencies remain unresolved. Systems still do not communicate effectively with one another. This has become the single largest bottleneck to meaningful AI-driven automation in FP&A.

In response, many organisations once again turned to the idea of building centralised data warehouses, expecting that consolidation would resolve most data challenges. This has been a recurring pattern for more than a decade. While substantial investments continue to be made in data centralisation, there is limited evidence that these efforts consistently deliver proportional business value, particularly for mid-sized organisations. In reality, these initiatives tend to be resource-intensive and are often feasible only for large enterprises with sustained funding and technical capacity.

As of 2025, the core data problem remains largely unsolved. Based on both experience and current observations, there is little indication that this will materially change in 2026.

Many expected 2025 to be the year when FP&A finally got a clear AI playbook, a standard set of use cases, repeatable patterns, and proven templates that teams could simply copy and deploy. That didn’t happen. One reason is that many of the most advanced AI use cases have emerged within large technology companies, where success has depended heavily on proprietary data, mature processes, and deep contextual knowledge. Those conditions don’t easily translate across industries or organisations.

Another reason is more cultural: some of the strongest AI implementations in FP&A were rarely shared publicly. They circulated quietly among peers, inside private networks, or within closed communities. And when they were shared, it was often only the successes, rarely the failures, false starts, or hard-earned lessons that actually mattered.

As a result, 2025 didn’t produce a universal checklist of “AI use cases for FP&A.” Instead, it revealed how dependent success is on context.

What Needs to Change to Turn Noise into Signal

If AI in FP&A is to mature meaningfully, the next phase requires clearer signals about what works, under what conditions, and with what trade-offs.

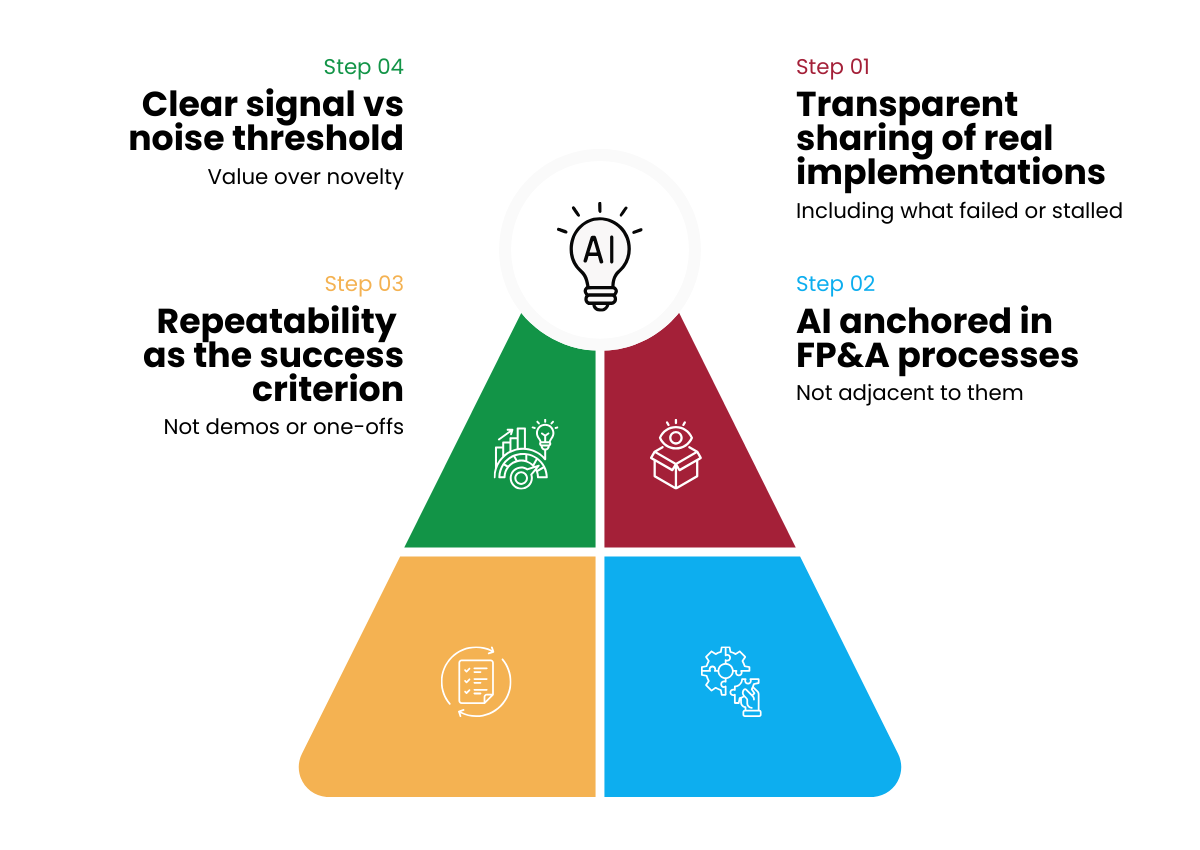

First, there needs to be more transparent sharing of real implementations. That includes what failed, what stalled, and what proved harder than expected, not just polished success stories. Without that context, teams continue to overestimate what can be copied and underestimate the effort required to make AI operational.

Second, AI discussions must be anchored more firmly in financial processes rather than tools. Close, forecasting, planning, and performance review workflows should define AI requirements, not the other way around. Without that grounding, AI remains adjacent to FP&A rather than embedded within it.

Third, repeatability must become the standard for success. One-off insights and demos are easy to generate. Sustained value comes from outputs that finance teams trust enough to reuse across cycles. That requires tighter integration, clearer data definitions, and explicit ownership.

Finally, FP&A leaders need better ways to distinguish signal from noise. The goal is not to adopt more AI, but to apply it where it measurably reduces friction, improves clarity, or shortens decision cycles. Anything that does not meet that threshold should be deprioritised.

Looking Ahead to 2026

As finance teams head into 2026, the opportunity is less about discovering new AI capabilities and more about consolidating what has already been learned.

The teams that make the most progress will be those that treat AI as an operating capability rather than a collection of tools. They will invest in ownership, process definition, and integration before expanding scope. They will judge success by consistency and trust.

If 2025 was the year AI became unavoidable, 2026 has the potential to be the year FP&A becomes more intentional about how to use AI.

Written by Ashok Manthena, who is a researcher and author on FInance AI topic. He is currently heading AI at ChatFin.ai.

Subscribe to

FP&A Trends Digest

We will regularly update you on the latest trends and developments in FP&A. Take the opportunity to have articles written by finance thought leaders delivered directly to your inbox; watch compelling webinars; connect with like-minded professionals; and become a part of our global community.